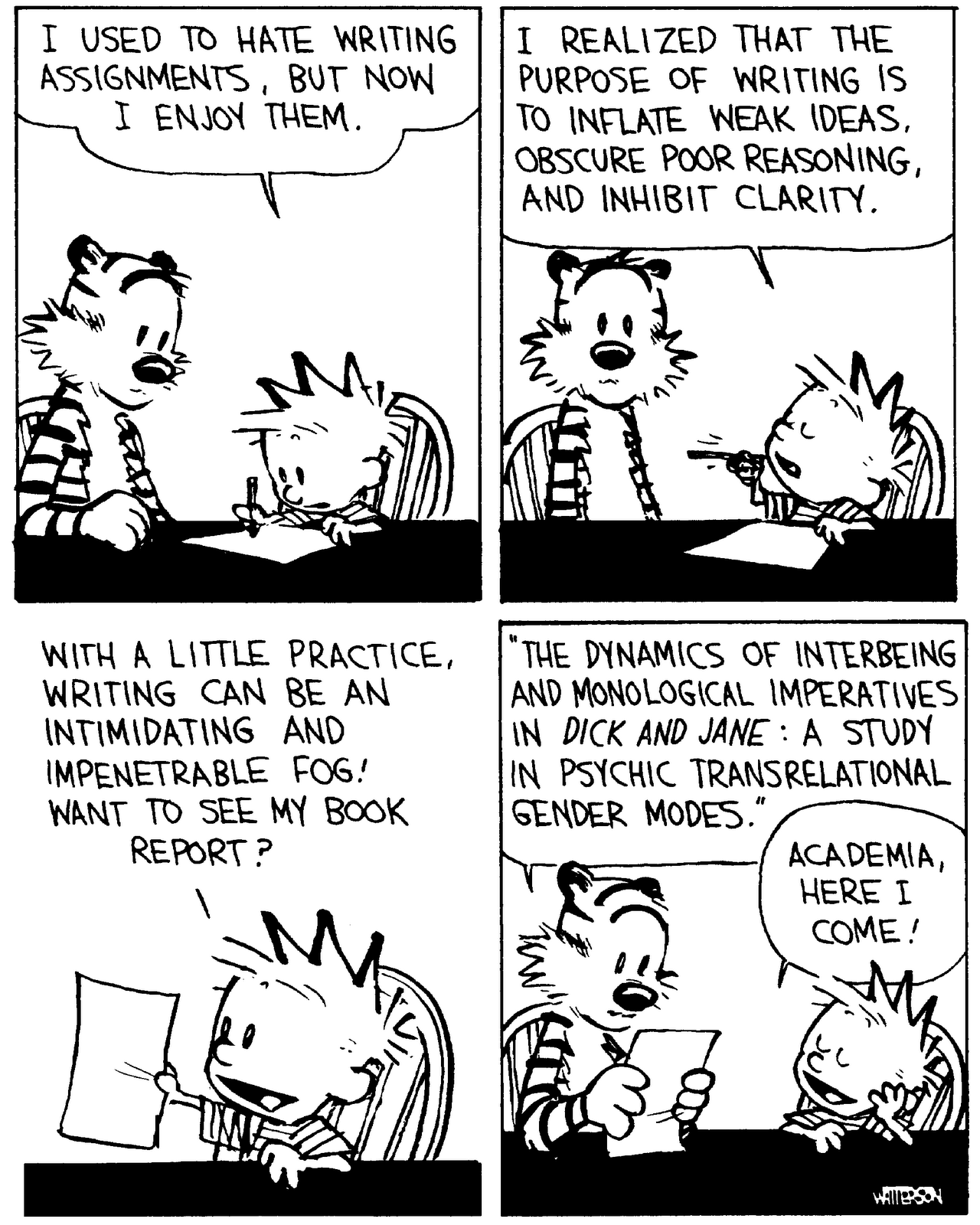

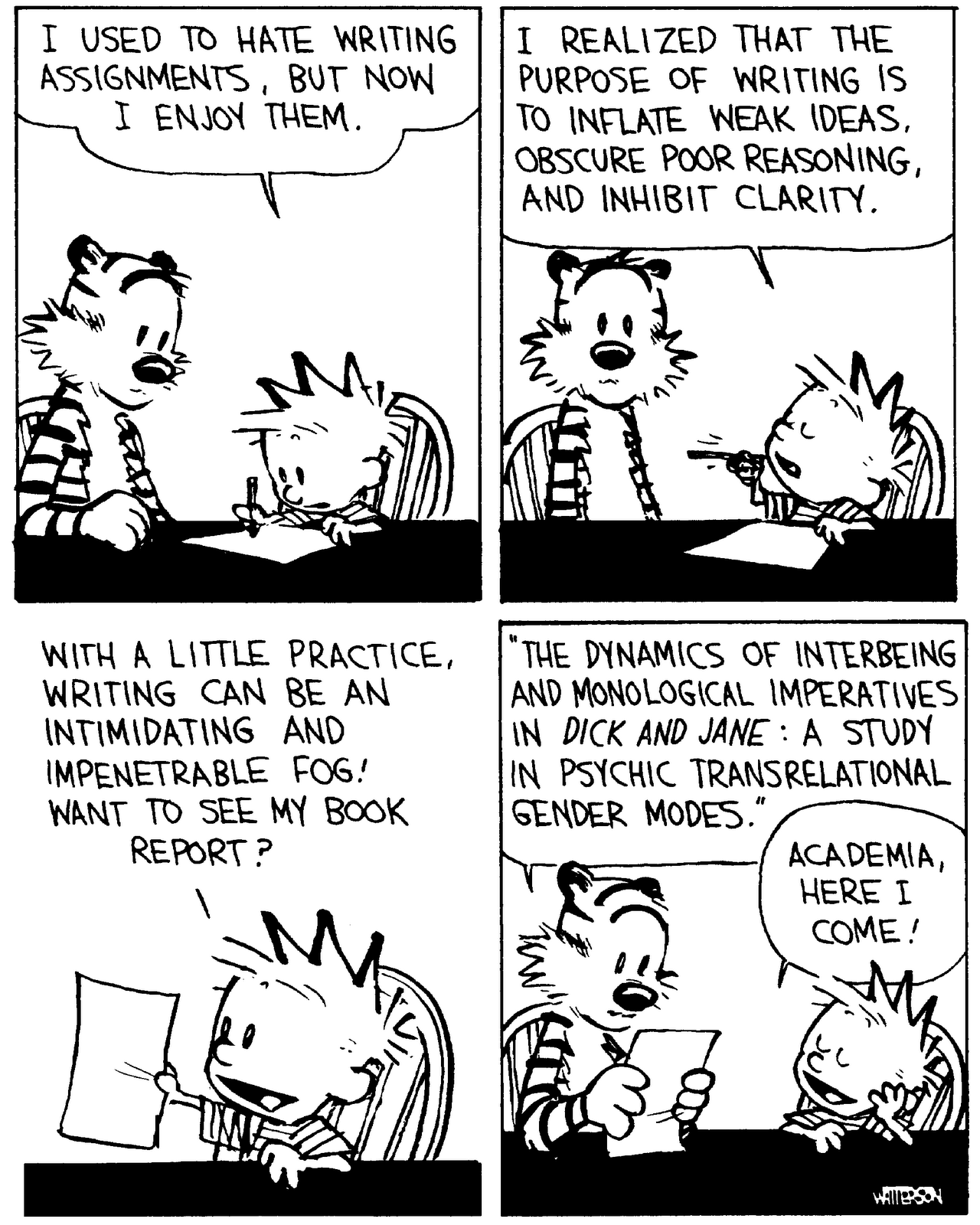

I said "It's called 'The Dynamics of Interbeing and Monological Imperatives in Dick and Jane: A Study in Psychic Transrelational Gender Modes.'"

I wouldn't have gotten the reference myself, so let me share this:

Strewed over with hurts since 2004

[A] question on the fourth-grade version of the test, which quoted three sentences from the 1858 speech in which Abraham Lincoln said, “A house divided against itself cannot stand.”I'd say reading comprehension goes a long way on a history test that asks you to interpret a text, and, more than that, the ability to read and interpret texts gets you much farther along in the process of learning history than knowing some historical facts.

The test asked students, “What did Abraham Lincoln mean in this speech?” and listed four possible answers.

a) The South should be allowed to separate from the United States.

b) The government should support slavery in the South.

c) Sometime in the future slavery would disappear from the United States.

d) Americans would not be willing to fight a war over slavery.

By reducing "diversity" to something as shallow and meaningless as appearance, they reinforce the most dehumanizing stereotypes of all -- those that treat people first and foremost as members of racial, ethnic, or social groups. Far from acknowledging the genuine complexity and variety of human life, the diversity dogmatists deny it. Is it any wonder that their methods so often lead to unhappy and unhealthy results?I think Jacoby is overdoing it here. I don't know why textbooks need to have so many illustrations and photographs in them in the first place, but that's a different issue. If you are going to fill up the pages with pictures of kids instead of useful information and analysis, you might as well display diversity and of course you should avoid the stereotypes.

[W]hen reality conflicts with political correctness, reality gets the boot.I'm taking that phrase "on occasion" to mean Jacoby didn't encounter enough of this sort of thing to highlight in his column. (Note what he does highlight: the terribly unshocking news that the children photographed in wheelchairs are often models who aren't -- as Jacoby politically incorrectly puts it -- "confined to wheelchairs.") There's nothing wrong with finding some heroines and heroes to offer some special inspiration to some children. But you can't do it too much or it's just obvious propaganda that isn't even going to work. It's fine to get out the message to young kids that, for example, a black woman can be a pilot.

So, on occasion, does historical perspective, as for example when a McGraw-Hill US history text devoted a profile and photograph to Bessie Coleman, the first African-American woman pilot -- but neglected even to mention Wilbur and Orville Wright. "A company spokesman," the Journal reports dryly, "said the brothers had been left out inadvertently."