The other post is about a city that "voted to name a park for a 1970 explosion that rained chunks of rotting whale flesh on curious bystanders."

So how often has "chunk" come up over the 16 years of this blog? Oh, maybe 50 or 100, but the most interesting thing is that one time, back in 2015, it came up twice in one day and I made it the word of the day:

"Chunk" is the word of the day here... for no other reason than that it's come up on its own twice: "invented something called the 'Cha-Chunker'" and "pegs in their hubs that can 'take chunks out of' the granite ledge." It's a funny word, isn't it? One thinks of "blowing chunks" or the "Goonies" boy Chunk or — if you're really old — "What a chunk o' chocolate":As for other uses of "chunk," there's Trump on June 12, 2020, also going on about Seattle: "They took over a city, a city, a big city, Seattle, a chunk of it. A big chunk."

The word "chunk" somehow devolved from "chuck" — the squarish cut of meat — and "chuck," like "cluck," is the English speaker's reproduction of the sound a chicken makes.

"Chunk" is a notably American word. Here are some of the quotes collected by the (unlinkable) OED:

1856 E. K. Kane Arctic Explor. II. i. 15 A chunk of frozen walrus-beef....

1833 J. Hall Legends of West 50 If a man got into a chunk of a fight with his neighbour, a lawyer would clear him for half a dozen muskrat skins....

a1860 New York in Slices, Theatre (Bartl.), Now and then a small chunk of sentiment or patriotism or philanthropy is thrown in....

1894 Congress. Rec. 13 July 7445/1 Just one moment, my friend. You are a lawyer... Yes, a chunk of a lawyer.

1907 Chicago Tribune 8 May 7 (advt.) It's really ridiculous the way we've knocked chunks off these Spring overcoat prices.

1923 P. G. Wodehouse Inimitable Jeeves xiii. 148 Eustace and I both spotted that he had dropped a chunk of at least half a dozen pages out of his sermon-case as he was walking up to the pulpit.

1957 T. S. Eliot On Poetry & Poets 49 Crabbe is a poet who has to be read in large chunks, if at all.

And I myself used the word only yesterday: "We — some of us — prefer the multicolored distractions of illusionism on the flat surface of the embedded video on Twitter as protesters drag down another stately chunk of metal."

This is also me, on July 5, 2018: "You know, out there in New York, California, and Massachusetts, they may think of the Midwest as a big undifferentiated chunk of flyover country, but to those of us who live here, our state (and even our region within the state) is quite specific."

In 2017, I wrote: "The corpse of Salvador Dali was exhumed to cut out some body parts to test to determine whether he was the father of a woman who's seeking a chunk of his estate." You can see that I used "chunk" there to create a poetic connection between the estate and the fleshly corpse.

Back in 2014, I had the occasion to parody Bob Dylan:

Well, that wigged art blondeIn October 2008, I said: "The most honest admission in the book, to my ear, was the confession that he spent a huge chunk of his formative years watching TV sitcoms with his (white) grandfather." I had just read Obama's "Dreams From My Father."

With his wheel in the gorge

And Turtle, that friend of theirs

With his checks all forged

And his cheeks in a chunk

With his cheese that says "ouch"

They’re all gonna be there

On that 82-million-dollar couch

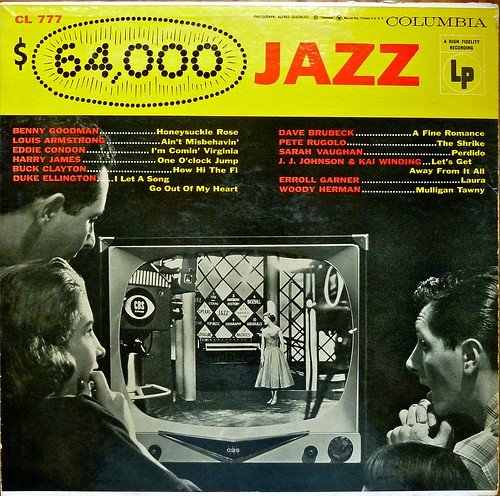

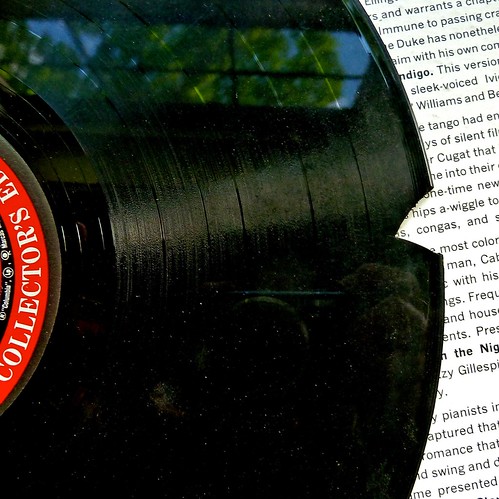

And speaking of "From My Father," I have something from my "Records From My Father" series. I said: "Unfortunately, this record, my 5th choice for this Records From My Father series, has a chunk taken out of it, and so I can't listen to Count Basie's 'One O'Clock Jump' or Dinah Shore singing 'Buttons and Bows.'"

What were all the other things? Mostly "chunk" appeared in quotes. The chunks tend to be of food, of time, of land or rock, and of money. I was pleased to see that in these years, I'd never once used (or even quoted) the trite phrase "chunk of change."