Is the author just dumping his thoughts on the page raw — expecting us to follow along? Or is this form perfection? Are you a strong enough reader to understand it on first read? Or is it better to read it, wander around in it, go over and over your favorite parts, then sweep through the whole thing?

When you do finally grasp it — sooner or later — does it seem to relate to American politics today? That's a whole second matter I'd like to discuss.

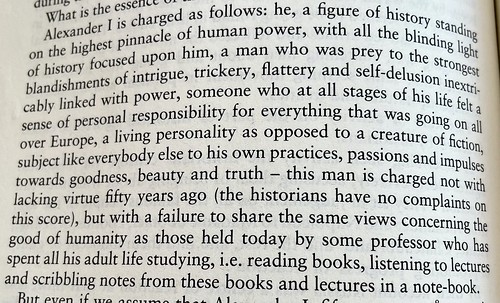

That paragraph was photographed by my son Chris. He and I have had conversations about the perceived problem of reading slowly, and I have taken the position that the best reading experiences have to do with slowing way down inside a single sentence. Of course, the worst writing slows you down too. The question is whether there's really something in there worth the journey.

५१ टिप्पण्या:

..does it seem to relate to American politics today?

Hell, Yeah.

Short answer. Average sentence length not too long.

Try reading anything from Jonathan Locke. His writing can drag on for pages.

I read about two shelf feet of Derrida copying every sentence into a notebook, as a way of slowing down.

The example is not a difficult sentence - it's all parallel.

Perhaps the author just isn’t a very good writer.

I doubt that Tolstoy "dumped" his thoughts raw here, I would bet this sentence went through many rounds of revision. And yes, I had no trouble comprehending it in real time. And yes, it seems to resonate with the kinds of cancel-culture, statue-toppling, issues we see around us today.

(Just for extra fun, though, I would highly commend to your attention the first sentence of Oliver Twist. It is the sort of sentence I pull up and read just for the pleasure of parsing.)

It takes a lot of historical background knowledge to digest that on the first read.

I can easily draw a conclusion that supports my preconceptions, and I suspect the same is true of those who disagree with me on almost any point I would make. The editor loved the author not wisely, but too well.

That sentence reminds me of: if you don't know how to tie a knot, tie a lot. It's a list in narrative form.

I do like a good long sentence that makes you train your brain. I go back to the one below for a refresher from time to time. It is a complete thought and did take a good amount of time for me to learn to slow down and comprehend each part to understand the whole. And this is Stimson when his writing was less complex. I first found an article he wrote, 'The Ethics of Democracy' published in 1887. It took a long time for me to really become comfortable reading it. It was compelling so I kept going back, but a very complex writing style. I don't know, maybe German-style where you had to read from both ends to the middle as you'd read a sentence only to discover it was completely opposite from what you thought he was saying when you got to the end.

But complex sentences, not just long ones, are how you train your brain.

"But no one, I think, has ever called attention to the enormous differences in living, in business, in political temper between the days (which practically lasted until the last century) when a citizen, a merchant, an employer of labor, or a laboring man, still more a corporation or association and lastly, a man even in his most intimate relations, the husband and the father, well knew the law as familiar law, a law with which he had grown up, and to which he had adapted his life, his marriage, the education of his children, his business career and his entrance into public life -- and these days of to-day, when all those doing business under a corporate firm primarily, but also those doing business at all; all owners of property, all employers of labor, all bankers or manufacturers or consumers; all citizens, in their gravest and their least actions, also must look into their newspapers every morning to make sure that the whole law of life has not been changed for them by a statute passed overnight; when not only no lawyer may maintain an office without the most recent day-by-day bulletins on legislation, but may not advise on the simplest proposition of marriage or divorce, of a wife's share in a husband's property, of her freedom of contract, without sending not only to his own State legislature, but for the most recent statute of any other State which may have a bearing on the situation."

--Popular Law-making: A Study of the Origin, History, and Present Tendencies of Law-making by Statute, Frederic J. Stimson (1910)

I rand this through one of those online reading level evaluation sites and it came out as reading level grade 99.

Tolstoy? If a sentence is big enough (and written by a great author), you can find real-world analogies to just about everything in it. Politicians are susceptible to flattery and self-delusion. Biden certainly is. I suppose he does have the same impulses as other people, but they were clouded over by 50 years in politics and a set of routines that he automatically runs through. 50 years in politics and his increasing senility isolate him from the normal human world.

If you're thinking Trump. I think he was too complicated. Yes, in one sense he certainly meant well, but his ego got too much in the way, as did his love of the show. Sometimes it seemed like the show was the thing, more than the real world results. Trump's views of the world certainly differed from those of the professors and the media and that accounted for much of his trouble with them. Obama was in agreement with the professors and the media. They were on the same page, but the susceptibility to flattery and self-delusion comes into play with him as well.

The political world does resemble Tolstoy's. People are too caught up in the political whirl and political routines to take much notice of the world beyond. Idealism and noble impulses perish in the need to follow the party line and fight the partisan war. Politicians do know enough to act empathetic and caring, but that's for the rubes who will buy it. Unfortunately, unlike Tolstoy, we rarely believe that there is some "true," "natural" way of behaving, and we know that if there were, we wouldn't find it among peasants.

"Slow reading" and "close reading" did a lot to put me off reading altogether. I have roused myself enough to dip into A.N. Wilson's biography of Tolstoy lately. Experts have criticized his books, but they are very informative for the rest of us.

I wonder how many people have the same problem I do, that's reading a passage that's particularly enjoyable over and over again. I do it because I enjoy reading those words so much, but it does slow me down. The better the writing, the slower I read.

This stream-of-consciousness speech from the mouth and mind of candidate Donald Trump lasted 90 seconds and was given to 500 people in Sun City, SC in July 2016.

“Look, having nuclear—my uncle was a great professor and scientist and engineer, Dr. John Trump at MIT; good genes, very good genes, OK, very smart, the Wharton School of Finance, very good, very smart — you know, if you’re a conservative Republican, if I were a liberal, if, like, OK, if I ran as a liberal Democrat, they would say I’m one of the smartest people anywhere in the world—it’s true!—but when you’re a conservative Republican they try —oh, do they do a number—that’s why I always start off: Went to Wharton, was a good student, went there, went there, did this, built a fortune—you know I have to give my like credentials all the time, because we’re a little disadvantaged—but you look at the nuclear deal, the thing that really bothers me—it would have been so easy, and it’s not as important as these lives are (nuclear is powerful; my uncle explained that to me many, many years ago, the power and that was 35 years ago; he would explain the power of what’s going to happen and he was right—who would have thought?), but when you look at what’s going on with the four prisoners—now it used to be three, now it’s four—but when it was three and even now, I would have said it’s all in the messenger; fellas, and it is fellas because, you know, they don’t, they haven’t figured that the women are smarter right now than the men, so, you know, it’s gonna take them about another 150 years—but the Persians are great negotiators, the Iranians are great negotiators, so, and they, they just killed, they just killed us.”

This is a sentence that, I think, works best read aloud. Read aloud, with the proper phrase separation (I grouped "inextricably linked" wrong myself, reading through) it seems pretty easy to follow. The insertion about 2/3 of the way through, of "this man" after a long dash is what makes it easy to follow. Without that, going "he [long series of appositive phrases] is charged" would suspend between subject and the verb too long, and I would tend to get lost. Restarting with "this man" helps make the overall organisation of the sentence clear.

I find it very easy to write very long sentences. It is sort of a stream of consciousness thing. I know lots of related ideas about the topic at hand and I just keeping adding them onto the sentence, each naturally flowing into the next. In my brain in makes sense. The sentences are, of course, almost unreadable. One of the most important writing skills I ever learned was to re-read everything I write, preferably a day or two later, both to see if I have overcomplicated the sentence and, perhaps more importantly, if I can still read it. Unfortunately, this does not lend well to comment posts, which need to get out sooner rather than later.

I do occasionally write really long, ridiculous sentences as a joke.

A very long sentence, but well-written, as it is very easy to read and comprehend in one go. I must assume the author wrote this long sentence to personify to the reader in his description the fullness to bursting of Alexander's achievements, responsibilities, and personal character.

Alexander wasn't woke enough.

No matter how many superlatives you add, every historical figure now falls prey to the same judgment delivered by lesser men.

Certain authors do require slowing down. I’m often too fast a reader, but I also do a lot of “light” reading, which allows for that. I do like to occasionally read something that forces the slow down. Austen is one. She has a tendency to throw in an important character note, plot point or fact in the middle of a long paragraph. I risk missing such things if I read too fast.

The passage does relate to today, where too many, with no consideration (or awareness) of context, find it too easy to judge harshly prominent persons of the past for expressing opinions or ideas that were culturally commonplace in their time but which are shockingly politically incorrect today.

when you're a bad writer, no sentence is too short.

the best reading experiences have to do with slowing way down inside a single sentence.

MY best reading experiences come from reading out loud.. No, not Listening; READING out loud.

The Lord of the Rings, is EXCELLENT to read aloud. The battle of the Hornburg at Helms Deep is a Pure Joy

It takes a while to say it all; but (towards the end), you ALMOST* feel sorry for the Orcs

ALMOST* i mean, you DON'T; they're goblins after all.. But: Alomst

I liked this sentence (Tolstoy?) better everytime I reread it.

I found Faulkner like that. I liked him much better the 2nd time I read his novels. His novels were also more enjoyable on Audiobook, where all the twists and turns and strange sentence structure, are perfectly understandable.

Sean Gleeson said...

Just for extra fun, though, I would highly commend to your attention the first sentence of Oliver Twist

Of course, if you Want to start a book out RIGHT; you really can't do better than

“I always get the shakes before a drop.”

The passage feels overly long and convoluted, but to truly know that, you would have to put forward a better version.

This version has a lot of emotional power because you feel you are being swept along in an inexorable wave that crashes and dissipates nicely into a snarky put down of a quibbling academic at the end. Good contrast between the majesty of Alexander and the nattering of the academic. Would you get the same effect if the passage were broken up more?

In the way that 19th century men wore mutton chop whiskers and women wore corsets with crinoline petticoats, so 19th century authors used semicolons and filigree dependent clauses. Styles change. Nowadays we pare things down. Thongs bikinis and shaved heads. The beau ideal is a declarative sentence with no adjectives or adverbs.....I like 19th century novels. Lots of interesting gimcracks stuffed in the curiosity cabinet. After a while you get used to the writer's rhythms and it flows easily.

I had no problem reading and comprehending the sentence, and find nothing in it to criticize.

The relevance of any description of a powerful historical actor's predicament to present times and actors is of course in the eye of the beholder.

Bleedin Whatney's Red Barrel

If you can't do the time, don't do the crime.

After wandering into the voice of Nick Carraway as I read, I knew I had to read it again, and again. Upon a second read I discover the sentence starts thus, "Alexander I is charged" and much later I see again "this man is charged...". Ok, it might a laundry list.

BTW. I don't ever remember making a laundry list. It must be just an expression. It might help to leave the long sentence for a bit, accomplish some minor task and comeback to the sentence. Theory holds that while I was doing the minor task, unconsciously to me the sentence was running a program or something analogous to a program decoding, plugging and stitching some blurry picture from the imagination of a person I never even met, but, because my brain is wired differently from that of the authors brain, not all the pieces of this giant puzzle meant to be put back together a certain way is going to be put back together that intended way by me. And that's ok too.

Alexander I had to deal with Napoleon, and his father and grandfather were murdered by their own subordinates, so he deserves some slack. That's an order or magnitude more dire than anything in American politics since the mid 80s, if not WWII.

That sentence was written by Anthony Briggs. There's another translation here if you scroll down to page 2.

The second one does a better job in some places, worse in others. The use of a colon after "influences" puts more emphasis on the problem, which is clearer to me, but is less hostile towards academicians towards the end, which is worse.

Another example, also from the first epilogue:

"Once you allow that human life is subject to reason you extinguish any possibility of life.

vs

"If we admit that human life can be ruled by reason, the possibility of life is destroyed."

I don't fully understand either of those. Maybe it made sense in Russian.

I didn't realize it was Tolstoy, so I spent time wondering if I'm reading about the Tsar or Alexander the Great.

It's amusing that, yes, we have idiots today judging the past through their chronocentric lens and of course they'll find them wanting.

As for Trump, my impressions of him are based more on what I saw around him. I rarely heard him speak, but I noticed that incomes rose across the board (especially for minorities), gas prices were at a good level, and his administration hit China by cancelling the U.S. Postal Office subsidies for products shipped from China to the U.S. (which was why my son was able to buy gee-gaws for which the postage was 99 cents, I s*** you not).

This was why Trump was a threat to the Establishment, and why they ginned up every fake scandal, why they released his taxes, and why they burned down cities and destroyed businesses, frequently minority-owned, to get him.

But let's get back to reading. When I was reviewing books, I received The Library of America's volumes on Henry James. In order to read enough to write a review, I had to find a quiet place and focus on the text. Regrettably, I can't remember anything I read, but I was impressed at the time with how much work I had to put into it.

Recently, I reread Lord of the Rings (first time since the 70s-80s). I made myself read everything, even the Tom Bombadil material and the songs. I came away with a far greater understanding of the book, the depth of his worldbuilding, and the tragedy he was describing. By the end of the book, we are in the world of men. Magic is dead, the elves are gone, the hobbits will go into hiding, and I felt bereft.

I'm going to go in a related direction. I used to teach composition. Talk about people being happy to see you! As I had older immigrant (trained in British schools, and also a few older returning moms who had attended parochial or pre-computer public schools, as I was), I was astonished by the relative incapacity of my young students to read and write and had read the classics and good popular fiction, even the clearly hard-working and bright ones.

Was it that screen time had dramatically reduced reading time? That no time wandering libraries and their web of books had ruptured cultural and literary discovery? I once asked a freshman class about their favorite authors. A few said Steven King or Michael Crighton. Most said they had never finished a book. As their 'Language Arts' workbooks mostly contained no more than a few paragraphs from any source, I am not certain they could understand the point of reading a whole book until Harry Potter came along.

In addition, are there ocular/neurological forces at play? I move my eyes across the pages of a book but scroll the words to meet my eyes on a screen. I believe there is a difference in cognition but have no proof of what it is. It feels more passive.

I have also noticed that newspapers and popular prose up to WWI or so resembles internet prose in style and voice far more than does written news and prose from appx. 1930 to, say, 2010.

JK Brown. Problem with that sentence is that you know where it's going about two words after the end of the first list of occupations or stations in life. Possibly that's because we live it every day (see Three Felonies A Day) as opposed to a time when it was a newish phenomenon.

I skimmed it super fast and got this: ignore the armchair quarterbacks and backseat drivers.

But I have been forced to find, read, and grasp critical knowledge as rapidly as possible in order to eat. Forgive me if I missed something.

As someone who specializes in poorly constructed run-on sentences, I thought it was perfectly readable, held a cogent thought, and yes, was political. It seemed to me to make a clear observation about those who use today's standards, such as they are, to judge yesterday's people.

If only we could get rebuttals from yesterday's people judging todays people by yesterday's standards.

Bill Peschel (12:38pm):

It couldn't have been Alexander the Great because he was Alexander III of Macedon, and it says "Alexander I". It could theoretically have been AtG's distant (century-and-a-half-before) ancestor, Alexander I of Macedon, but no one except a few ancient historians cares about him.

Too many comments here attempt to extract too much vague flummery from too few words without noting the sentence is about a specific person in a specific time.

The Alexander is Emperor Alexander I, Tsar of All the Russias, Grand Duke of Finland, Hetman of the Don Cossacks, etc, etc.

Considering the general conditions in Russia at the dawn of the 19th century, Alexander was remarkably liberal-minded, at least until the Congress of Vienna. He was the son of Paul I, one of the weaker tsars, but as the son and student of Catherine the Great, he raised a well-educated, reform-minded tsarevich in Alexander. However, the possibility of the abolition of serfdom evaporated in the aftermath of Napoleon's final downfall. Alexander came under the influence of the arch-reactionary Klement von Metternich after a small cabal of rebellious officers tried to overthrow the Romanov state by kidnapping Alexander while on the road to Belgium to negotiate the restoration of the Bourbons. The emperor who rescued Russia from Napoleon devolved from hero to tyrant in a matter of a few years. In his efforts to preserve the Romanov dynasty, Alexander was compelled to make supportive alliances among the most powerful landowners, rather than the powerless intellectuals, putting the liberation of the serfs beyond the pale of feasible politics. The last years of his reign created the conditions leading to the first serious revolutionary movement, the Decembrists rising against his heir Nicholas I, the worst Russian autocrat since the absurd Peter III. Until the attempted coup d'etat, Alexander was a Tsar ahead of his time, but mutiny and practical politics intervened to make him a typical Romanov reactionary.

The sentence is reminiscent of woke politicians who would love to destroy America's respectful gratitude to her Founders because their moral assumptions do not jibe with theirs, as if today's outrageous scolds and statuary vandals have achieved the summum et optimum when the cognizance of the past ought to inspire humility. If a wise person is tempted to exalt his prejudices into virtues, he wonders whether future generations will damn him as a barbarian.

An easy read. I just wanted to know who he was. Probably not Alexander the Great. But he never did ID him.

Thanks for that Trump quote gadfly.

I still rather have Trump and his stream of consciousness than this Biden with an embarrassingly infantile cheat sheet.

A period in place of the em dash ("truth - this") would have made for two perfectly OK sentences.

An Emperor who was at the center of life of his times is being judged (poorly) by a bookish, arrogant hermit. I took this to be the meaning of the sentence on first reading.

On the topic of fast and slow reading, I would mention the heuristic puzzle. The puzzle is this: You can't understand what the first words of a sentence mean till you read the last words but you can't understand the last words of the sentence till you understand the first. Yet we understand sentences.

Gombrich, an art historian, wrote about such paradoxes back in Sixties and from him I derived the idea that you should read long sentences quickly to get a global idea of the meaning. In other words you should get to the last words quickly so they can come to bear on the first words. Then, maybe, re-read, slow down.

OK, on rereading the photographed sentence I now see that: The Emperor who was the center of the cultural life of his times is being charged by historians with not holding the same views as are common fifty years later among professors who spend their time in libraries and (implied) this sort of charge is idiotic.

The sentence does relate to American politics today because people of both yesterday and today are being judged on whether they are exactly in step with Twitter=based wokie mobs. But it is not exactly parallel because most of the people being judged are just regular citizens, not Emperors. Think of that woman on a plane to South Africa right at the start of Twitter mobbing who sent off a "joke" on Twitter, got on a plane, and got off hours later with her life ruined by a Twitter mob. A life ruined while she was airborne and didn't even know what was happening and could not defend herself. And the mob thought that was the best part of it all - "She doesn't even know we're ruining her," they boasted. And the same has been attempted thousands of times and done - well, there's no count of how many have been the victims of such mobs. Can such such behavior establish justice and secure tranquility? Or did James Madison, who wrote the US Constitution by the light of candles held by slaves, propose a better foundation for a better pattern of behavior with more room for both freedom and necessary change?

Tolstoy reads like Hemingway compared to Faulkner.

For fun, here is the sentence diagram of the first sentence of the Declaration of Independence (71 words):

http://www.german-latin-english.com/diagramdecind1.htm

Dr Weevill: I stand (well, sit) corrected. It's been many years since I took ancient Greek history and learned about the old boy.

"The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire" by Edward Gibbon is composed of long sentences bunched together in even longer paragraphs. Some paragraphs span more than one page.

It's the bad books and the fast, sloppy, careless readers who keep the publishers in business and the novel a living genre in spite of the best efforts of literary novelists to kill it. When poetry came to only be for highbrows, the masses turned against it and it ceased to be a living genre with real appeal to readers. The lowbrows were driven out, but most of what's written now is more coterie or workshop/industrial than actually highbrow.

I didn't read slowly or carefully, but I didn't think Tolstoy was attacking Alexander. In his hierarchy, while most of high society were fops and parasites, a well-meaning emperor who saw his country through a terrible war and tried to make what he thought was a good peace might stand above mere academics and bookmen, though "bookman" would certainly describe Tolstoy himself.

I rarely read the comments. And I’m glad I did this thread. Thanks.

Tolstoy was no mere bookman (I say as one who finds the old fellow boring most of the time).

In the passage he seems to echo Hegel, who warned against "the schoolmaster's trick": subtly leading his listeners to the conclusion that he is greater than Alexander [of Macedon] because he never conquered the known world.

OK the writer’s name was Tols Toy. Sounds Russian to me. The sentence was perfect, but I bet the characters had several nick names just to torture the readers. That sounds like Hillary.

It's a perfectly clear sentence.

I understand it’s form very well- w/it’s dashes and parentheses.

It reads like he’s thinking the sentence through.

I very fond of dashes and parentheses.

I’m very appreciative for the History lesson, too, as well as all the explanations.

टिप्पणी पोस्ट करा

Please use the comments forum to respond to the post. Don't fight with each other. Be substantive... or interesting... or funny. Comments should go up immediately... unless you're commenting on a post older than 2 days. Then you have to wait for us to moderate you through. It's also possible to get shunted into spam by the machine. We try to keep an eye on that and release the miscaught good stuff. We do delete some comments, but not for viewpoint... for bad faith.